Reply: Philosophy and "Misinformation"

|

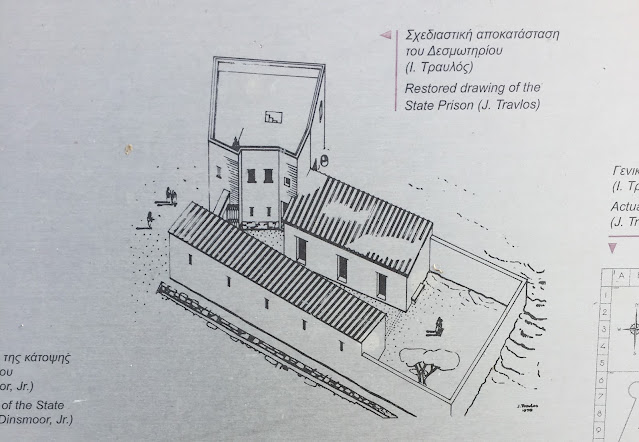

| Drawing of the State Prison in the Agora where Socrates is thought to have died. |

The following is a reply to The Philosophy Club's event, "Philosophy and Misinformation go way back..." and the linked write-up for context; however, I tried to make most of the argumentation understandable without context:

https://misinformation.henid.com/

I think it is an interesting claim to consider that “Philosophy is facing a frontal attack.” Though this seems like an empirical question in which may be impossible to distinguish “what” is being attacked. How can the complex practice of world philosophy be measured? Are philosophy departments under changing stress? However, it seems the qualification here is that the practice of philosophy consists in “asking questions,” and that certain polemists in society are attacking philosophers—or are we all philosophers attacking each other and don’t know it?

(The Free-Speech debate on college campuses might be a good case example to consider what the political debate is about. Though this steers us away from the original question of “philosophy.” Still, even Neil Levy suggests that not giving some speakers a platform improves “higher-order evidence,” which is also an important concept in consideration for the epistemology of testimony.) https://www.cambridge.org/core/journals/journal-of-the-american-philosophical-association/article/abs/noplatforming-and-higherorder-evidence-or-antiantinoplatforming/C4A92DB3795DF24768F4D618EA596D37

So what about “questions?” I am not sure what word is the right desideratum for judging questions (permissible, appropriate, allowed, reasonable, better)? (The current example of what Fox News and Tucker Carlson are being accused of doing is saying that "we are just asking questions" about claims that are not based in any justifiable foundation/evidence...essentially conspiracy). There are of course the old challenges of "question begging," but that usually means you are avoiding asking the "right" questions. (Abortion is murder; no, Is Abortion Murder?; what?, but Is Abortion the Devil stealing souls?). Hence, we can distinguish as to the permissibility of questions in the philosophical domain and between the public domain in general. However, this begs the question as to whether these two domains are really separable or at least where the demarcation exists. OK, so what is the right question to ask?

Moreover, we can still have a debate as to which philosophical questions are better, acceptable, or worthy in a supposed spatiotemporal context. I usually lied when I said to my students that there are “no stupid questions” —but this concerns the “authenticity” of asking questions: If I genuinely don’t know/understand something or am confused about something, then your mind could generate a question, and then you could formulate a linguistic expression and then verbalize it (I am not assuming this is the actual cognitive serial process). You could also just stare back at the teacher with that confused face because you don’t even have a question. Appropriate questions function in a linguistic context, and philosophers are said to be the best at formulating questions in order to clarify something. “Just asking questions” arguably can be viewed as a form of bullshit or part of the action of misinformation spreading. This is because it is possible to pollute the epistemic health of social practices: if any bizarre claim or question is permissible in the “infosphere”, then how can you be open-minded and test your convictions to relevant alternatives if the internet has made many more alternatives radically available? It has the opposite effect of making you more closed-minded (S. Goldburg 2010).

The essence of Victor’s inquiry seems to be trying to get to the heart of what could be reframed: What is the role of the “public” philosopher and its relation to the broader question of pedagogy and politics (the normative question of democracy, the common good, and truth as a social good)? Is the role of the philosopher to contribute to more opposing views, theories, arguments; and/or, to find ways to improve the epistemic health of society and its social institutions?

Therefore, reference to the very acts of Socrates is important: not really because of why he was found guilty of corrupting the youth, but the way in which he was doing it. If the conception of Socrates/Plato’s pedagogy is that of the unkempt, smelly guy walking around “getting into arguments and debates” with people in the Agora, then we have the conception of the public philosopher as no different than the Sophists that did the same thing—they were not usually silenced, or put to death. Why? Is it because Socrates was actually effective. He was the one who was actually dangerous to the status quo. Simply put, he engaged in on new dialogic method, the ἔλεγχος (Elenxus), as a form of Maieutics (Midwifery). This is different than the conception of philosophy as rational debate and evidence giving. The best argument and analysis of this is from L. Barthold’s recent book, which can be referenced for a complete expansion of the analysis, and connects to a larger research project that I am engaged with in relation to public education and pedagogy; but in brief: The rise in polarization in politics and the public square, along with recent research on the problems of rationality (e.g. Haidt and Kahneman), shows that we need a form of public discourse focused on dialogue:

“This book argues that where polarization is predominant, traditional forms of rational argumentation and reason-based persuasion will likely prove impossible. But that does not mean we need to “reach for our guns” and give up on civic discourse all together. Instead, we need to utilize a form of discourse that is specifically tailored to reducing polarization by first building trust and creating mutual understanding.”

Moreover, Barthold’s close reading of Plato and Arendt are worth reading fully: you can find this selection at the end of this text. Here is the full copy of the book:

https://link.springer.com/book/10.1007/978-3-030-45586-6

This does not replace the need for rational debate, deliberation, and policy making in the public square of a democracy, but it reframes the discussion about what precisely are our social and epistemic goals, and what is the role of philosophy (or probably more specifically, the philosopher) within public discourse. Moreover, the questions and problems of deceit, misinformation, and propaganda still remain; but perhaps the worry about Victor’s conception of the Public Philosopher can be deflated.

What Victor’s analysis fruitfully yields: a discussion on how we ought to believe. So the problem in today’s society is a problem of polarization and arrogance, particularly what Lynch calls intellectual arrogance, and hence the need for intellectual and epistemic humility (Lynch, 2020). In Know-it-all Society, Michael Lynch tackles the main problem of how to deal with the destabilization of recognizing facts themselves—how can we rationally argue if we don’t even agree on what counts as facts? A theory of 'convictions' and forming beliefs might be an answer: we are all infallible but also must have convictions to act; but, “how can I be open to the possibility of being wrong while still maintaining strong conviction?” (p. 13). Moreover, Lynch’s understanding of intellectual arrogance mirror’s Victor’s strategy of the misinformationists: “an unwillingness to regard your own worldview as capable of improvement from the evidence and experience of others…and also put ego before truth—but tell themselves they are doing the opposite”(23).

Shutting down inquiry:

Let’s continue with the structure of Victor’s argument and analysis: Skepticism is also a common concept in epistemology, that we can not know, in general or specific domains, with differing levels of certainty; while modern cynicism deals with the disposition of disbelief in the good and unselfish motives of others and society writ large. Victor argues that if free inquiry is shut down systematically by the new tactic of “misinformation” as euphemism, then more cynics will exist, and the necessary epistemic trust breaks down. The notion of shutting down inquiry, debate, free thinking, critical thinking, free speech, and the like, all have deeps roots in the history of societies and the formation of corresponding governments. Jason Stanley, in How Propaganda Works, makes this very claim about propaganda: it’s ability to shut down democratic critical debate. His point is that the beliefs of the demos/ or the audience of propaganda are the tools in how propaganda works.

“First, I will give examples of propaganda in which someone is being misleading, rather than stating something false, or even implicating something false. One expresses a truth, and relies on the audience’s false beliefs to communicate goals that are worth-while. Falsity is implicated in such cases, but not by means of the expression or communication of a falsehood. I argue that propaganda depends for its effectiveness on the presence of flawed ideological belief. But it simply does not follow that the flawed ideological belief that makes some claim effective as propaganda is expressed or communicated in that claim” (Stanley, 2015).

It seems reasonable to me that the category of “misinformation” could also fall under this analysis, in which misinformation functions in a way that steers people way from the democratic norms of debate, discussion, and por lo tanto, away from the democratic ideal of common good deliberation and the search for truth. Victor, though, is on to something here: how should we analyze philosophical inquiry and misinformation? (Again, assuming for the sake of argument that the public philosopher is an agent that is suppose to engage in rational inquiry, question engaging for the sake of debate. Moreover, Victor moves into an analysis of social power structures and a theory of rights, which I will not address here. This move, however, does show the divergent philosophical approaches, which again, probably has something to do with our individual levels of cynicism. There are also hints of Foucault’s approach to the archeology of knowledge and biopower.)

Deceit Framework:

Victor makes a very interesting claim in reverse of the usual discussion of misinformation: the “misinformationist” is the one who claims that something communicated is misinformation in order to shut down inquiry. I generally agree that there are co-opting strategies in public discourse that try to throw off the rational discourse by using some kind of fallacy charge: a parallel example would be Trump calling whatever news outlet he did not like as “Fake News,” while the term originally having a valid purpose of identifying the real existence of news/information that was completely fabricated. Or a coded usage of “be civil” to mean “shut up.” But what is that “something” that is being called misinformation?

So, is the framework of {Lies, Bullshit, Misinformation} as the main forms of deceit missing something? First, I think a clear analysis of “Information” could be helpful. Adding “misinformation” with the traditional normative categories of speech acts of lying and bullshit seems off to me: this is because lying and bullshit usually have a clear single agent involved. More importantly (and being a little nit-picky), is that misinformation as deception seems to be a serious danger to epistemic health, and lying is not exactly or necessarily a form of deception. Though I may want to deceive you by lying, I can lie to you without deceiving: what I say could accidentally be true (Lynch, 2020, p33). Moreover, like a shell-game, with propagandists and misinformation, “they just have to get you confused enough that you don’t know what is true…and by not believing what is true.” (ibid). Hence, refer back to the issue of social epistemic health if too many alternatives glut the system, and dismantle healthy epistemic alternatives and good evidence.

Moreover, our epistemic, virtual, “internet of us” world is a very complex and new environment. Of course, many of the same epistemology problems that philosophers have discussed since Socrates are still in play; but as Lynch has persuasively argued, we are living in a world in which massive amounts of information, google-knowing, and instant connectivity are at our fingertips (not everybody, there is epistemic inequality—which is a major problem for epistemic justice). This recent TED talk is a good place to start: (he also shares all his work on Academia)

Lynch claims that Truth is both an epistemic goal and a democratic goal:

https://www.academia.edu/75445582/Truth_as_a_Democratic_Value

Also: Victor’s uses “epistemic enhancement” without a clear articulation of what that entails and why that is valuable. Perhaps latter on in his argument…but the hint of epistemic relativism remains.

So if we don’t have a functional category of “misinformation” (and disinformation, fake news, malformation, propaganda,…) then how can we explain a vast array of phenomena: Edgar Welch and Pizzagate, QAnon, Mike Daisy, the NSA, False flag claims, Troll Farms, algorithmic “agents”, and the broader issue of information glut and pollution?

Another approach suggested is to approach the problem of deceit and inquiry suppression is to look at a theory of meaning and communication (as approached in the philosophy of language). Particularly, Wittgenstein’s theory of language games. I am sympathetic to a more Wittgensteinian approach to the nature of misinformation, as seen then as a part of the broader theory of Communication and Meaning. It is possible that Victor’s analysis presupposes a kind of “propositional-knowledge transference theory,” (or a referential theory of meaning in the minds of language users) by which rational agents engage in one-to-one encounters with other rational agents, and can transparently compare mental propositional representations through argument formation, and hence can decide rationally how they want to modify their epistemic credence toward proposition P or ~P.

Wittgenstein wanted to replace a theory of meaning with a “conception in which to use language meaningfully is to master a certain kind of social practice. (Soames, 2003). Moreover, the language game, then, is to master a social form of rule following in which meanings of words and expressions are determined (usually unconsciously) but the already consensus by the linguistic community. There are some serious problems with Wittgenstein’s arguments for basing a ‘rule following’ theory of meaning, especially since there is no internal psychological state of understanding a word-meaning (see Kripke’s Rule following paradox). So, perhaps in line with a more contextual based approach, I would propose an approach with the philosophy of information, or information theory.

So let’s go back to “Information”: how does a theory of information help us understand the reality that we live, epistemically and normatively?

Claude Shannon’s mathematical theory of information (1949), is a statistical relationship between different states of affairs in the world: What can be gleaned about state A for the observation of state B? Causally related in varies ways (richness) and can be measured independently of what the info is about. (Dennett p. 106). But within human understanding, we what Semantic Information, the aboutness of the quantified bits that we could theoretically measure. What is semantic information? Like the word “In form ation” - Something’s being in formation is just for it to be non random. (Floridi, SEP). Semantic Information is non random distinction that makes a difference (with a difference) (Dennett and Floridi). But can it still be measured? Robert Wilson in sci-fi proposed the “Jesus unit”. Defined as the amount of scientific information (no contingent historical, what Pilate had for breakfast info) known during the lifetime of Jesus. So how many Jesus do we ‘know’ today. Shrug.

From the evolutionary stance, “Semantic Info as design worth getting” might help us here. Disinformation is designed (don’t need a designer) for the benefit of one agent of another agent’s systems of discrimination, which themselves are designed to pick up useful information and use it (Dennett p.118). Viruses and bacteria “deceive” your cells—and we don’t even have to assume that these replicators have “intentions” or are epistemic agents.

Though brief, it looks like a robust theory of information can help us understand the networked and contextual nature of misinformation and its epistemic impact. Moreover, sharing information, especially on social media or the internet in general, can function in complex ways that can include issues of blame and intention, but also non-intention and still deception.

We can now see Wittgenstein’s insight: the communication of information takes many forms, and also has an added confusion with we look at sharing information online. Both Wittgenstein and JL Austin with the ordinary language school showed that expressions are also speech acts, so many forms of communication should be seen as doing something within the established communication game. For example, questions, commands, descriptions, assertions can all exist as speech acts; but also can overlap each other in the context of speech acts, like in telling a joke or expressing dislike for something as both expressing anticipation, desire, and endorsement. In all these cases information is being transmitted, but with information comes noise and the receiving parties will only receive and interpret the information that they are able to with the evolutionary tools that they have (including physical, cognitive, cultural, and conceptual—sound waves could possibly cause a flower to vibrate, but the flower does not have the “tools” to decode the information and use it, since the plant does not need it from an evolutionary standpoint).

Dennett has used the poem “Not Waving but Drowning” Stevie Smith to illustrate semantic information: the person who is out in the ocean water drowning, and flapping his or her hands. The people walking by on the beach see the person “waving” and wave back. The birds circling above, however, are decoding the information differently. https://www.poetryfoundation.org/poems/46479/not-waving-but-drowning

Bubbles and Chambers

Though the internet and social media are a “testimony network,” it is still very difficult to know who are the real epistemic agents. Algorithmic delivery systems and “bots” that pose as real people creates the illusion that other testimonials exist. Whether or not we are in a epistemic bubble or an echo chamber, how can we even evaluate the higher-order evidence that they are trust-worthy, reliable or have human rationality? Levy’s argument also seems to assume that 1) echo chambers are the natural state and should be (2 the internet age makes no difference in epistemic, Bayesian belief formation (His only evidence for this assumption is a study that says conspiracy theories have not increased since the advent of social media (from 2014!). Perhaps the reason for a lack of measurable changes to conspiracy theory belief is 1) how do you measure that? 2) Micheal Sherman’s theory of patternicity. https://www.ted.com/talks/michael_shermer_the_pattern_behind_self_deception )

Though I think the bubble/chamber framework is a useful conceptual tool, it also creates the acceptance of this kind of metaphorical theory that the structural of reality just are these “enclosures.” It still takes us back to the previous question of how we know who are the epistemic agents in the first place, and then how do we even know which chamber we are in, and who or is not pre-encountered before we “get” into our chamber. Do we exist in multiple chambers, that cross penetrate each other? Using Victor’s metaphor: how do we know when we are in fact looking out or looking in? Yes, of course, in our idealized epistemic network we have are rationally justified to trust our in-group because we believe are in-group is less likely to deceive. However, how do we know who is really in our in-group, and not just kind-of in our group, or deceivingly in our group? (It makes me think of recent surveys about Catholic Clergy or theologian students who secretly claim they are atheists).

Instead of Bubbles and Chambers, Bryan Frances (2011) uses another, but similar framework for disagreement: Recognized Epistemic Peers and Recognized Epistemic Superiors. However, this raises questions of how you establish in the first place who has the exact same evidence, intelligence, or education on a particular claim that P or ~P? Still, this framework helps in the evaluation of the normative questions: “under what conditions should I change my mind? Or “does it matter that one agent was on the right track in the first place…?). Again, credence or probability of belief can be utilized: in which a Bayesian approach can help decide the scale of changing your mind. Again, this analyzes ideal contexts with rational agents, and not necessarily the empirical questions of what humans are really doing with their beliefs.

The “Illusion” of Evidence Based Medicine.

What examples are there of the claim that suppressing information/speech by calling out “misinformation” is done by “power concentrations” (States, corporations, the rich)? (Though I will discuss a couple of Victor’s examples, my analysis tried to demonstrate that a worry about power structures and social epistemology can be deflated, and that polarization and epistemic trust are more of an issue).

Science and Ivermectin: Sure, the human sciences have always had an “operationalization” problem, and that medicine is even more value-normative-laden, but precisely because medicine, and even more pandemics, are policy and population-conscious dependent, they are always in a future oriented and reactionary dialectic (there is not a public "dark-matter policy”): who decides which interpretation of the data that the average person does not understand to dictate into policy (what, everyone, should do their own double-blind study?) In the Ivermectin case, the original “lucky” selection helped to cause the added public health crisis of people taking it on their own. If this did not happen (counterfactual randomness), then it is possible that noone would have to do more studies on it, because there would have not been a new public health crisis (emergency?). So the illusion is that there is even a possible “disinterested” party to do research. Though according to the release of the NEJM study in the NYT, many “random” drugs were being tested for effectiveness for COVID-19, so in the history of things, there just so happened to be evidence that Ivermectin had a positive effect in large dosing…and for the public, the cat was already out of the bag (probably not Schrodinger’s cat): How should “health experts” evaluate the scientific health effects of releasing “information.” Can we do a double-blind, unfunded study on that?

What about the RCT study that was “disinterested” and double-blind: “Assuming the D-RCT is a gold standard in biomedical science, the blindness helps to compensate for the deficiencies of its smaller size.” What does Victor mean by “compensate,” and how would a non-scientist evaluate the credence and impact on your own beliefs and the debate about public policy? And yes, what should be the gold standard?

Medical expertise, science-based medicine, evidence-driven research… all these notions presume that people really want to understand what is good for them and are willing to make the necessary adjustments. But this is mistake. People want pills and jabs – not diets, muscle aches, nor anything that may give pause to their mortality denialism. And if the pills are too old, or the jabs too few, to generate the funds to make newer and better pills and jabs, where is the sense in that? Bottom line: these people know what is good for us. We don’t. All else in misinformation.

This begs the question of levels of moral paternalism in medicine and health policy. Moreover, it misses the distinction between individual health and public health. Still, I respect Victor’s analysis as a skeptic and cynic, which ideal science has already built into its structure. What is generally unclear is the connection to debates within the scientific community and whether all “information” about ALL studies are “released” to the public for every individual person to evaluate on their own in their own bubbles/chambers to decide which studies they would prefer to use: in other words, there should be no such thing as Public Health Policy other than complete transparency and everybody (or every bubble/chamber?) must decide for themselves. No mandates whatsoever, right?

Finally, it is still unclear to me what in this case is actually being labeled as misinformation? The studies themselves, which in analysis, could have possible answers within a good theory of information and misinformation; or, is the very act of sharing particular studies, links and memes itself labeled a misinformation (in context of an actual exchange of two people or on comments on social media)—maybe even by the very social media site itself? Were any studies or commentaries cited by Victor ever taken down by Facebook or labeled as misinformation? If so, that would perhaps help his case. If you are shut down by sharing information that you think helps public debate, why did that happen to you? In my view, the information channels of our infosphere are broken and polluted, and more work needs to be down rebuilding trust networks through dialogue.

Masks Effectiveness?: https://www.povertyactionlab.org/evaluation/impact-mask-distribution-and-promotion-mask-uptake-and-covid-19-bangladesh

Randomized, controlled trial. Gold standard. Moreover, Victor’s arguments are coming from confidence levels of some kind of beliefs about evolutionary biology and microbial spread expertise? Masks can do harm? Really? Cause we are not getting the “good” microbials?

Bullshit or transparent misinformation

I think Trump has psychopathy, but the “inept” claim needs clarification. To use “skill knowledge,” even if Trump was inept at many, many other things, it doesn’t follow that he was inept at all the above: bullshit, misinformation, propaganda, and yes, lying. Going back to the “Not Waving but Drowning” case: there is a possible world in which ALL the information transmitted to the rational party at the beach seemed most likely in context to be just waving. It is difficult to build a theory of meaning and communication that assumes that any ideal rational and discriminated agent can always know the “truth” of a communicated message, they just need proper education. The drowning person was not intending to communicate to the birds above that “I will be food soon.” Victor’s claims about doxastic discrimination are very interesting and I would propose we push this line of reasoning farther. Still, we are missing “higher-order evidence” here, and moreover, as Victor I think would agree, a broader analysis of the structure of democratic deliberation, epistemology and education. At least for the Trump example, it seems Victor blames “representative democracy” or the power structure’s ability to create the illusion of rights, freedoms, demo— instead of polarization, arrogance, and a broken infosphere. Again, this is where much of our frameworks diverge.

______________

Dialogue and the Polis (From Chapter 1 OPPS, by Lauren Barthold)

The belief that where rational argumentation proves impotent the only recourse is violence is one that is challenged in the opening section of Plato’s Republic. Inviting us to consider a third way, the encounter between Socrates and Polemarchus reveals something about the political potential of dialogue and its capacity for moving us beyond the violence versus rational persuasion dilemma.17 It is also a way of highlighting the importance of connecting with another on the level of meaning as opposed to just facts, a point that will be deepened by Arendt’s analysis with which I close this chapter.

Recall that Socrates and Glaucon are returning from a religious ceremony in the Pireaus and preparing to leave town when they meet up with Polemarchus, who orders them not to leave and instead to come spend the evening at his house. In fact, he is so eager to have Socrates join him that, after sending his slave boy running ahead to grab hold of Socrates’ tunic to implore him to wait, Polemarchus resorts to threatening Socrates with violence, saying: “Do you see how many of us there are? Either prove stronger than these men or stay here.” The choice is starkly put: Socrates and Glaucon can either use force to overpower this larger group of men or else submit and go to Polemarchus’ home. Is not this sentiment precisely what underlies so much of our contemporary public discourse where political debaters use words to fight their opponents? Indeed, many politi- cal debates are now cast as sports competitions—“the first fight is in the books”—where candidates are described as “trading body blows.”18 I

17 All quotations in this section are taken from Plato 1991, 3–4 (327a–328b).

18 See CNN coverage of the July 2019 second round of Democratic debates (https:// www.cnn.com/opinions/live-news/commentar y-night-2-of-democratic-debate-june-27/ index.html); also see https://www.cnn.com/2019/09/12/politics/who-won-the-debate/ index.html Additionally, the New York Times constantly focused their reporting on “who won” the debates: https://www.nytimes.com/2019/06/27/us/politics/democratic- debate-winners-losers.html; https://www.nytimes.com/2019/06/28/us/politics/debate- winners.html; https://www.nytimes.com/2019/09/12/opinion/democratic-debate- houston.html

want to take a closer look at what happens next in order to appreciate Plato’s relevance for considering an alternative response.

In his reply to Polemarchus, Socrates tries to avoid violence by advocating the power of persuasion: “Isn’t there still one other possibility... our persuading you that you must let us go?” But Polemarchus—perhaps representative of those who find philosophy impotent in the “real world”— retorts by exposing the fatal flaw of persuasion: “Could you really persuade [us] ... if we don’t listen?”19 Indeed, some consider the refusal to listen as a form of violence.20 As a result, violence, or a threat thereof, is made to appear even more politically expedient than persuasion since it does not require the impossible task of getting the other to listen against their will. Where no-one is listening, shouting and violence tend to be the default strategies. Before Socrates has a chance to respond, Glaucon jumps in to cede Polemarchus’ point and says: “There’s no way.” Polemarchus then triumphantly responds: “Well, then, think it over bearing in mind we won’t listen.” Given that persuasion proves impotent when others refuse to listen, and since Polemarchus has just admitted that he refuses to listen, it appears that Socrates and Glaucon are back to having to choose between either utilizing or submitting to violence.

Or are they? I want to argue that the falsity of the dilemma between persuasion (represented by Socrates) and violence (represented by Polemarchus) is proved by Adeimantus’ subsequent intervention. For note what happens next: Adeimantus turns to Socrates and begins to describe to him the novel torch race on horseback and all-night festival that is set to occur that evening, thus engaging Socrates in a friendly con- versation that shifts the focus by inviting him to consider some points of interest he had not previously thought of. Adeimantus’ efforts to build bridges and reveal common interests are hallmarks of dialogue. In other words, Adeimantus appeals to the personal interests and desires of Socrates in describing the events of the evening. Socrates replies with genuine

19 If Hannah Arendt is correct in her assessment of Plato’s disappointment with persuasion after Socrates’ failure before the jury (Arendt 1990, 73), we might read Polemarchus’ question as motivating the whole Republic-as-“dialogue” that ensues: namely, how is the philosopher to respond when persuasion proves impotent?

20 David Bohm describes the violence experienced when one is not heard: “in general, if somebody doesn’t listen to your basic assumptions you feel it as an act of violence, and then you are inclined to be violent yourself...” (Bohm 1996, 53).

interest to Adeimantus saying, “On horseback? That is novel. Will they hold torches and pass them to one another while racing the horses, or what do you mean?” Adeimantus’ clever dialogic intervention—exemplary of the most skilled facilitator—highlights common interests that help turn the interaction away from a stark win-lose scenario. His words invite a new interpretation. Even Polemarchus joins in and he adds further details including the promise of dinner and conversation. Glaucon then (again) concedes: “It seems we must stay.” And this time Socrates con- firms, saying, “if it is so resolved, then this is how we must act.”

I think we can conclude from this exchange that in spite of the lack of rational persuasion attempted by Socrates and Glaucon, they did not sim- ply submit to a threat of violence. For Adeimantus describes the evening’s events in a way that shows them to be meaningful and of interest to Socrates. As a result, Socrates and Glaucon decide to remain—but not out of the fear of the threat of violence but because a common and shared interest has been discovered. Adeimantus thus disproves the very assump- tion Polemarchus had articulated and that Glaucon (and Rorty) had initially and (too) quickly agreed to: namely, that submission to the threat of violence is the only alternative when rational persuasion seems impotent. Nothing in the text indicates that it was submission (i.e., the fear of violence) that dictated Socrates’ and Glaucon’s ultimate decision to remain in the city. What we witness was a type of communication that appealed neither to pure logical argument nor to (threat of) violence. On offer were activities of genuine interest to Socrates that helped him notice the commonality and congeniality of the evening’s events.

I begin with this close reading as a way of setting up my preliminary definition of dialogue, to be developed in subsequent chapters, as a spoken interaction that opens a common space for listening to and acknowledging the desires and interests of another in order to achieve mutual understanding. Dialogue is a form of interpersonal exchange in which each participant’s desires and interests are offered up and received in such a way to reveal a commonality. Its goal is mutual understanding. Putting it in Platonic language that I shall further clarify below by way of Arendt: it is a way of forging connection through sharing “opinions” that reveal the deeper, universal “truth.”21 In other words, I am categorizing

21 As Chap. 2’s analysis of Martin Buber makes clear, “universal” and “commonality” are existential rather than epistemic terms in so far as they describe our fundamental connection to the other.

Adeimantus’ words that offered a friendly appeal to, in Dewey’s terms, the “desires, interests, and purposes” of Socrates, as elucidating the essence of dialogue. Yet while dialogue might be fine among friends who meet in the road, is it fit for the polis?

To help us ponder in more depth the political relevance of dialogue and its ability to discern truth in opinion, I turn to Hannah Arendt’s essay “Philosophy and Politics.”22 Arendt contends that Socratic dialogue was an important and novel practice that utilized opinion. She writes: “Although it is more than probable that Socrates was the first who had used dialegesthai (talking something through with somebody) systemati- cally, he probably did not look upon this as the opposite or even the counterpart to persuasion, and it is certain that he did not oppose the results of this dialectic to doxa, opinion” (80).23 What I want to focus on, though, is her point about the relevance and role of doxa, particularly how she goes on to note that “the word doxa means not only opinion but also splendor and fame. As such, it is related to the political realm, which is the public sphere in which everybody can appear and show who he himself is. To assert one’s own opinion belonged to being able to show oneself, to be seen and heard by others” (80).

Arendt further develops her claim that dialogue elicits doxa, and thus appearance, in her analysis of the maieutic nature of dialogue: “What Plato later called dialegesthai, Socrates himself called maieutic, the art of midwifery: he wanted to help others give birth to what they themselves thought anyhow, to find the truth in their doxa” (81). And she goes on to reflect:

22 Let me clarify that my analysis does not require me to defend Arendt’s public-private distinction. In fact, it is my hope that my reflections offer a way to complicate her problem- atic distinction, which Seyla Benhabib has termed her “phenomenological essentialism” (Benhabib 1992, 94).

23 As Arendt construes it, political persuasion is a form of violence (although oddly and incorrectly she pits persuasion against compulsion [74]). She writes: “To persuade the multitude means to force upon its multiple opinions one’s own opinion; persuasion is not the opposite of rule by violence, it is only another form of it” (79). Perhaps she has in mind Gorgias’ statement that if Helen of Troy had been rationally persuaded to leave her home, as opposed to physically abducted, it still would have counted as an act of force. Additionally, John Sallis uses persuasion as one form that nous’ generation of the world takes (Sallis 1999, 91). In any event, “persuasion” had a variety of different meanings in Greek, and therefore I do not find it problematic that she considers dialogue as a form of persuasion.

Yet, just as nobody can know beforehand the other’s doxa, so nobody can know by himself and without further effort the inherent truth of his own opinion. Socrates wanted to bring out this truth which everyone potentially possesses. If we remain true to his own metaphor of maieutic, we may say: Socrates wanted to make the city more truthful by delivering each of the citizens of their truths. The method of doing this is dialegesthai, talking something through, but this dialectic brings forth truth not by destroying doxa or opinion, but on the contrary reveals doxa in its own truthfulness. The role of the philosopher, then, is not to rule the city but to be its ‘gadfly,’ not to tell philosophical truths but to make citizens more truthful... Socrates did not want to educate the citizens so much as he wanted to improve their doxai, which constituted the political life in which he too took part. To Socrates, maieutic was a political activity, a give and take, fundamentally on a basis of strict equality, the fruits of which could not be measured by the result of arriving at this or that general truth. (81)

There is a lot to unpack here but let me start by saying that Arendt helps us regard with suspicion the idea that structuring a discourse to allow the maximum number of truths to be proclaimed is always the best way to improve a democratic discourse. A debate in which each side prof- fers its best truths to “destroy” their opponent’s opinions is not the Socratic ideal of politics-as-education. Arendt seems to be suggesting that the successful polis is not defined by its end, that is, consensus, or arriving “at this or that general truth,” but by its means, that is, dialogue. For only dialogue can create a truly public and equitable space. The philosopher here is not assigned to the role of ruler but rather that of midwife.

Furthermore, I think we can extend Arendt’s emphasis on Socrates’ maieutic endeavor by maintaining that the maieutic activity lets what is appear, but that this can only happen with the involvement of another person. And although birth and appearance require another person, namely, a midwife, the midwife does not threaten or rationally persuade the infant to be born; her role is to encourage what already is to come forth. Descartes, alas, was no midwife and “truths” are not that which are most self-evident, clear, and distinct to one’s own mind. In a time of political, social, and religious turmoil, it is neither Descartes’ “man who walks alone and in the dark” nor our contemporary social media warrior who can return us to truth. Rather, we need a midwife who elicits appearance, birth, without recourse to disembodied reason alone or threat of force. In fact, as Socrates reminds us in the Symposium, birth can only take place in the presence of beauty and tranquility. That truths are not proclaimed and

argued for but revealed, elicited forth from doxa (81), insures their meaningfulness since they are seen to emerge from a particular embodied individual as well as a particular socio-historical milieu. Too often in our frustration with fact/truth-deniers we forget Dewey’s point about the need to attend to the meaning of facts, that is, to recognize that they are tied to particular socio-historical and embodied interests. As finite, embodied, historical beings we cannot do away with doxa and expect to get straight to “the truth” and “the facts”—as the image of the solitary thinker suggests. The implication here is that “midwife” needs to replace “meditator” as the dominant epistemic metaphor. Dialogue is that practice that allows us to take opinions-as-embodied-meanings seriously.

Arendt also draws our attention to the fact that by allowing the opinion of another to come together with one’s own opinion, dialogue generates a community of equals in so far as no single opinion is exalted as truth. Dialogue is the antidote against individual opinion congealing into “truth- as-a-final-end-point” since it entails the ongoing examination of all opinions. In addition to avoiding a fixed hierarchy with a single regnant truth, dialogue also prevents the unhappy state of relativism where everyone sim- ply votes for his or her own opinion as truth. It is precisely this sort of relativistic pluralism that prevents a functioning polis that Plato feared and that motivated him to seek a better form of dialectic—one grounded in an ongoing dialogue that produces a commonality between interlocutors rather than any specific conclusion, truth, or consensus.24

Arendt reads Socrates as demonstrating that dialogue is that form of citizenry that builds the community by establishing what is held in common, what lies in between. Such a dialogue creates a “commonweal” revealing what is held in common, shared, and “between” citizens in order

24 Arendt writes: “Plato was the first to use the ideas for political purposes, that is, to introduce absolute standards into the realm of human affairs, where, without such transcending standards, everything remains relative” (1990 75, emphasis added). Yet she admits, and I agree, that Plato never intended the ideas as purely political much less as standards, if by standards we mean knowable criteria by which to measure and judge. The realm of the forms, rather, functioned as an image to indicate a type of regulatory ideal, an impossible-to- achieve telos of human existence, a liminal image—not a blueprint or set of measurable criteria. Plato’s defense against the relativism of the Eleatics was not to summon a knowable creed but to show us that without an imagined telos, human life is meaningless. Without a highest truth, rationality is impossible. Yet as Socrates’ words imply again and again, we can never know with certainty, clarity, or distinction what these forms are. The good is beyond being, beyond conceptualization. See Barthold (2010), Chap. 5 for a protracted argument about the role of the good in Plato.

to sustain an equality. Walls and laws may be able to protect or secure what already exists, but they can never create the equality necessary for true community. Dialogue cultivates the continued growth of community; walls enshrine a community and thus constrain it. It is important to stress here that Arendt saw the possibility for creating a “commonweal” as funded by difference. Dialogue requires, and does not seek to eradicate, difference. Equality does not mean that everyone is identical but that “they become equal partners in a common world—that they constitute a community” (83). Arendt concludes, “The political element...is that in the truthful dialogue each of the friends can understand the truth inherent in the other’s opinion... Socrates seems to have believed that the political function of the philosopher was to help establish this kind of common world, built on the understanding of friendship in which no rulership is needed” (83, 84).25 For Arendt, the political relevance of dialogue is its ability to aid one in seeing how the world appears to one’s friend, thus enacting both commonality and equality.

I want to clarify, however, that what Arendt is expressing here is not some form of cognitive empathy. To see the truth in another’s opinion is not merely to be able to reiterate their beliefs. Spewing back the talking points of one’s interlocutor does not necessarily guarantee connection (or meaning). If dialogue is indeed an active and ongoing process that creates community, we need more than mimesis. I take Arendt’s point to be that there is a type of human interaction that is beneficial for creating a community in so far as it evinces a shared perspective, requires equality, and allows the other to appear. Both dialogic partners stand on equal footing in the realm of appearance. Such a community of equals cannot be established by rational argument alone—particularly that form of rationality we call instrumental—but neither does it require force. Arendt explains:

On this level, the Socratic ‘I know that I do not know’ means no more than: I know that I do not have the truth for everybody, I cannot know the other fellow’s truth except by asking him and thereby learning his doxa, which reveals itself to him in distinction from all others. In its ever-equivocal way, the Delphic oracle honored Socrates with being the wisest of all men, because he had accepted the limitations of truth for mortals, its limitations through dokein, appearances, and because he at the same time, in opposition to the Sophists, had discovered that doxa was neither subjective illusion nor

25 See Nicomachean Ethics 1155 a 20–3. See also Allen (2004), which defends a form of political friendship as central to a thriving democracy.

arbitrary distortion but, on the contrary, that to which truth invariably adhered. (85)

Dialogue is that form of interaction in which we continually engage the other in genuine questions about her doxa in such a way as to allow her to appear. Such engagement would require much more than cognitive empathy in the sense of knowing the thoughts of the other. Dialogue is a pro- cess that trades in more than facts and does not seek out a final truth; it serves to establish, generate, and continually make visible what is in common.

Arendt concludes her reflections on the political potential of philosophy with a section on wonder. She claims that for Plato the beginning and end of philosophy is wonder, which is a general, wordless, existential form of questioning. Unlike scientific questions that are easily put into words, aim at the particulars, and explicitly address practical concerns, philosophic wonder is aimed “above” and in its generality renders one speechless—as exemplified by Socrates’ stupendous moments of wonder that paralyze him, preventing him from speaking and walking. Because of this speech- lessness, Arendt maintains that wonder removes the philosopher from the polis, whose realm is speech and action. I contend, however, that she is incorrect to suggest that Plato insists that philosophy must end in speech- less wonder. For the dialectic Plato develops is grounded in Socratic dia- logue that, as we have seen, remains ongoing. It is dialogue’s very ongoing nature that preserves the distinction between sophists and philosophers. As Arendt’s earlier analysis has revealed, Socrates does not take opining in and of itself as a bad thing; rather, it only becomes problematic when opinion is treated as the final and complete telos. Socrates demonstrates in his dialogues how a genuine openness toward another keeps a degree of wonder active to the extent to which it prevents one from taking one’s own doxa as truth. If one is truly trying to understand how the doxa of another appears to her, one cannot persist in claiming that one’s own doxa is truth. As Arendt has rightly maintained, there is nothing wrong with possessing doxa so long as one does not defend it as truth. In fact, doxa, as a form of appearance, is what dialogue trades in.

Against Arendt I want to argue that dialogue should be understood as a way both to prevent us from converting doxa into a (pseudo) truth and to prevent us from remaining in speechless wonder. If both wonder and doxa are legitimate facets of human nature, then dialogue can serve as a form of dialectic that keeps us from getting stuck in either one of these

two components. We need others who can help prevent us from taking our own doxa as truth, which returns us to the experience of wonder. The new opinion we hear another expressing can break us out of our routine wordiness and make us pause in wordless wonder. This is a necessary step in so far as to keep speaking and defending one’s own “truth” can silence the other, denying their capacity for acting and speaking. But neither should we remain in wordless wonder, no matter how tempting and appealing it may be. For Plato’s allegory of the cave instructs us that it is unjust for the philosopher to remain in the sunlit bliss of speechless wonder. Justice demands that the philosopher return to the realm of doxai and engage others so that their doxai might also undergo a review. Dialogue is the form that such dialectical pedagogy takes in so far as it requires more than a single individual to enact. As such, dialogue is the closest we can get to a life of pure wonder and the closest we can get to truth—yet we never quite arrive. And this is the life that Socrates modeled. Yes, we wonder at ultimate truth, as Arendt puts it, but we are also language-using, social beings whose speech reveals our desire to connect with others and so we try (are compelled) to put truth into words, and the result is doxa. When the other encounters our doxa, she is motivated to consider how it accords with her doxa, and is provoked to wonder, where wonder entails a degree of speechlessness in so far as one is not trying to argue against anything in particular that the other has said. In its generality, wonder promotes the openness required for true dialogue, and Arendt notes how the power of wonder derives not from rational argumentation but from an existential encounter (98). Opposed to wonder is the desire to win that drives debate and requires a focus on defending and attacking particular claims in order to come to a conclusion. We could also oppose wonder to instrumental inquiries that seek the best means for a given end. Wonder, which occurs according to Arendt only when existence is at stake, incites the general ongoing dialectic of dialogue and prevents anyone from claiming to have won a specific argument (98–99). Against Arendt, however, I am arguing that it is the tension between wonder and doxa that motivates dialogue, particularly dialogue of a political sort: one that connects us with another and in so doing creates a public space, a viable pluralistic polis. A life of pure wonder is unfit for mortals with social needs. After all, even Socrates had to pause from his wonder and come in and join the feast and conversation with friends; friends (and food) are necessary accompaniments to the philosophic journey.

For Socrates, the practice of philosophy-as-dialogue never comes to an end, reflecting the endless plurality of humanity. Plato sought to ground dialectic in Socratic dialogue in a way that maintained the anti-relativist thrust of his forms while at the same time acknowledging human finitude and fallibility. Taking seriously Platonic forms does not imply that we can reach or know them, much less that we can allow dialogue to come to an end in wordless silence. As the myth of Er suggests, even physical death does not put an end to the need for philosophizing, since it proves useful in choosing our next life. For that reason, I detect a political relevance in Plato’s account of dialogue that I maintain already meets the conditions Arendt spells out in her concluding paragraph of the essay I have been exploring:

If philosophers, despite their necessary estrangement from the everyday life of human affairs, were ever to arrive at a true political philosophy they would have to make the plurality of man, out of which arises the whole realm of human affairs—in its grandeur and misery—the object of their thaumadzein. Biblically speaking, they would have to accept—as they accept in speechless wonder the miracle of the universe, of man and of being—the miracle that God did not create Man, but ‘male and female created He them.’ They would have to accept in something more than the resignation of human weakness the fact that ‘it is not good for man to be alone.’ (103)

I take Socratic dialogue to be affirming precisely this sense of plurality: not only do we exist in a plurality but we are finite beings for whom plurality proves beneficial. Wondering alone, by oneself, is not philosophy—at least not the sort of philosophy endorsed by Plato and Socrates. Our human condition of finitude and plurality requires us to situate that won- der in an appropriate form. Dialogue is just such a form in so far as it invites us to wonder along with others and to consider their doxa as important and fallible as our own.26

26 My criticism of Arendt here might seem to help explain a failure in her theory of judgment that Benhabib notes: “Where I depart from Arendt though is in her attempt to restrict this quality of mind [judgment] to the political realm alone, thereby ignoring judgment as a moral faculty. The consequences of her position are on the one hand a reduction of princi- pled moral reasoning to the standpoint of conscience, which is identified with the perspective of the unitary self, and on the other hand, a radical disjunction between morality and politics which ignores precisely the normative principles that seem to be embodied in the fundamental concepts of her own political theory like public space, power and political community” (1992, 141).

In conclusion, I have appealed to the interpretation of Arendt to defend my claim that in the opening scene of the Republic there is something significant revealed about dialogue’s political potential. Before being able to build their ideal city in the private space of Cephalus’ home, these friendly architects needed to establish a foundation suitable for such a city. As the “prefiguration of the whole political problem” (Bloom 1991, 441), their encounter in this opening scene teaches us that the ideal city is to be founded not on violence or persuasion but rather on dialogue.

______________________________________

WORKS CITED

Barthold, Lauren. 2020. Overcoming Polarization in the Public Square: Civic Dialogue. Switzerland: Palgrave Macmillan Springer Nature.

Dennett, Daniel. 2017. From Bacteria to Bach and Back: The Evolution of Minds. New York: W.W. Norton & Company, Inc.

Frances, Bryan. 2011. “Disagreement.” In The Routledge Companion to Epistemology, edited by Sven Bernecker and Duncan Pritchard. New York: Routledge.

Goldburg, Sanford. 2010. Relying on Others. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Haidt, J. 2012. The Righteous Mind: Why Good People are Divided by Religion and Politics. New York: Pantheon Books.

Lynch, Michael. 2016. The Internet of Us: Knowing More and Understanding Less in the Age of Big Data. New York: Liverlight Publishing.

____________. 2020. Know-It-All Society: Truth and Arrogance in Political Culture. New York: Liverlight Publishing.

Stanley, Jason. 2015. How Propaganda Works. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

Soames, Scott. 2003. Philosophical Analysis in the Twentieth Century, Vol 2. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

Sequoiah-Grayson, Sebastian and Luciano Floridi, "Semantic Conceptions of Information", The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy (Spring 2022 Edition), Edward N. Zalta (ed.), URL = <https://plato.stanford.edu/archives/spr2022/entries/information-semantic/>.

Comments

Post a Comment